Christmas celebrations in the 1840s were very different than they are now. For most of the poor Irish laborers, it was a day away from work. This gave them an opportunity for some time with their families. In good years, parents would provide a special treat, an orange, a bite of cheese or a hen that could be roasted over the fire. But no matter the year, this was a day without pay.

The Martin family was financially secure, so the worries of a payless day did not dampen the holiday. Often, they entertained the Harshaw family and other neighbors for a holiday breakfast. This tradition was followed in 1846 despite the famine that was engulfing Ireland at the time. After this happy gathering was ended, some participants attended a funeral for Mrs. Murdock.

Gathering together of family and friends was the single activity for most Irish families to mark the special day. There were no religious activities unless the holiday fell on the Sabbath. In 1847, Christmas fell on Saturday. John Martin hosted the family breakfast in his home, Loughorne House that year, unaware that he would never be able to do that in Loughorne again. In the afternoon, John and his Uncle Harshaw went to their offices to pay their workers. This was a dark and deadly year for Ireland, and no one was in a position to wait for their pay.

Still, other activities took place to make the most of this day without work. Children played shinney on the lanes of Loughorne and Donaghmore. This was a game somewhat like hurling where children hit stones with curved sticks. Horse races across the fields and over the hedges occupied the horse lovers of the area. Orangemen took the opportunity to show their shooting skills in local competitions, the two events colliding in Ballyroney and resulting in the murder of Hugh McArdle in Ballyroney. (For an account of this, see post Death in Ballyroney.)

The great Irish famine raged across much of Ireland from 1845 into the 1850s. Few died in 1845, thanks to aid from the British government. But by the next year, many were already either dead or experiencing Christmas in a different land. The Martins and the Harshaws celebrated the holiday with heavy hearts ever thereafter.

Sources: Diary of James Harshaw, 1846 - 1850. Vol. One and Two.

[Updated with link]

I wish all my followers a very Merry Christmas and Happy Holiday. May you experience the joy of family gatherings that marked the day in Ireland.

Marjorie Harshaw Robie

Saturday, December 17, 2011

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Toward a New Nation

On April 15, 1840, the great Catholic leader in Ireland, Daniel O’Connell, announced his next political project. He would lead a great Irish movement to nullify the Act of Union of 1800 which made Ireland English. “I have the delight to feel that I shared in the struggle for the liberation of my country from the shackles of the penal enactments, but my heart never beat as warmly for Emancipation as it now does for Repeal.”

John Martin found the new Repeal Association growing when he returned from America. Despite his strong desire for Ireland to be free and independent, John did not hurry to join the O’Connell movement. There was much work to occupy his time. He was an active and generous landlord, and a leader in his local Presbyterian Church. And he took on his first political assignment, one much closer to home.

The Poor Law which John so strongly opposed had established a new system of care for the poor peasants of Ireland. All help for the poor laborers of Ireland would be provided in prison-like Poor Houses. Funds to pay for care of each inmate were provided by a tax on the farmers of each Poor Law District. A Guardian was elected by the taxpayers to watch over the management of the Poor House and keep the taxes as low as possible. John had been elected Guardian for Ouley, the Poor Law district designated for Loughorne.

John hated everything about his job. He hated the idea of the law which placed all the cost of maintaining the poor people of Ireland on the backs of the farmers of Ireland. People with businesses and family income paid nothing. He hated the sight of the huge Newry Poor House which hovered over Newry like a angel of death. In fact, many who entered died of rampant diseases. He hated that families were divided on entry through the tall walls that surrounded the new facility, wives from husbands, children from parents. But most every Saturday when the Guardians met at the administrative building to conduct of the supervision of the poor, John was there.

Not long after the Newry Poor House opened in December 1841, the first link in the chain of events that led John into national political leadership took place in Dublin. One day in the summer of 1842 in Phoenix Park in Dublin, three friends, two Catholic, and one Protestant, sat in the shade of a large oak tree to discuss an idea new for Ireland. Charles Gavin Duffy, John Blake Dillon, and Thomas Osbourne Davis had met in the Repeal Association meetings. These men were a bit younger than John and full of energy and ideas. Each of them had previous experience in the newspaper business, and saw the need for a new kind of newspaper, devoted to Irish nationality. This paper would educate the Irish people about their heroic history and thereby promote a new pride in their country. Before the men left the park, they had agree to try this new venture.

Charles Gavin Duffy would be the editor of this new paper, having already been the editor of a newspaper in Belfast. Thomas Davis was the visionary heart of this project. He believed that Irish, Protestants and Catholics alike, should unite for the good of their shared country, that it was a desire to be Irish that made each person Irish, not family history or time in country.

|

| Thomas Osbourne Davis |

|

| Charles Gavin Duffy |

|

| John Blake Dillon |

Newspapers were the best source of information sharing in Ireland. Each paper reached many people, as they were passed from the purchaser to many more friends and neighbors. Someone would bring his copy to the local pub and read the papers aloud to the many laborers in the area who were illiterate.

The first edition of each new newspaper contained an early version of a mission statement. The Nation, as the editors chose to name their paper, had nationality as “their first object – a nationality which will not only raise our people from their poverty, by securing to them the blessings of a domestic legislature, but inflame them with a lofty and heroic love of country.”

Duffy, Dillon and Davis set up their new enterprise at 12 Trinity Street in the Temple Bar section of Dublin, almost within the shadow of the Castle, the seat of British power in Ireland. Daniel O'Connell liked the idea of a new weekly newspaper, as long as it was produced by some of his own young followers. In fact, John O’Connell, Daniel’s son and designated successor, was to be a contributor.

The first edition of the paper was published on Saturday, October 15, 1842. As soon as enough papers had been cranked through the large presses, stacks of them were handed over to newsboys who raced to their favorite corners to begin hawking the new paper. The Nation proved easy to sell, not a single copy being left in Dublin by noon. More papers were printed and shipped by carriage to important towns around the country.

John’s childhood friend, John Mitchel and his family were at this time living in nearby Banbridge. After some indecision about a career. Mitchel had become a lawyer. His practice took him frequently to Dublin. On some of his trips, he visited the Repeal Association meetings, and had actually become acquainted with the new editors of the new Nation. Not surprisingly, he was most interested in reading the new paper as soon as the first copy reached Banbridge. When he finished reading the paper, Mitchel sent it over to Loughorne, so John could read it.

When the Mitchel family, John, his wife Jennie, and children came to Loughorne to visit, the two men had much new material from The Nation to discuss. Though they were firm friends, the two men strongly disagreed about political affairs. Mitchel was fiery and passionate, while John was much restrained and thoughtful. Their friendship took them into strange places and down different paths. But it never faltered.

On one thing the two men agreed, the importance of The Nation. It helped propel John Martin from the quiet and peaceful country life he preferred into a life of political service his country.

Sources: Wikpedia, The Nation; The Newry Commercial Telegraph, Letter of William Harshaw, 1835, April 24, 1841; Life of John Mitchel, by William Dillon.

On one thing the two men agreed, the importance of The Nation. It helped propel John Martin from the quiet and peaceful country life he preferred into a life of political service his country.

Sources: Wikpedia, The Nation; The Newry Commercial Telegraph, Letter of William Harshaw, 1835, April 24, 1841; Life of John Mitchel, by William Dillon.

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Bastards by Queen's Bench Decree

A great new controversy swept over Ulster in the last summer of 1841. At that time, John Martin was taking another trip, this time east to Europe. The insult to his Presbyterian religion which was causing great anger amongst his friends and neighbors was waiting when he returned. No need for him to abandon his time in Belgium, Germany, and Italy to return home.

Every August, summer court sessions, Assizes, took place across Ireland. No one foresaw the problems that would flow from a minor court case in the Armagh Assizes. A rather uncouth man named Samuel Smith was on trial for bigamy. The facts seemed straight forward. He had married Jane Gordon from Portadown in 1839. Since he had had married another woman 8 years before, the court case seemed routine. And it was except for the unique defense Smith mounted. He claimed that his first marriage was illegal as he was a member of the Church of Ireland, and any marriage with a Presbyterian, performed by a Presbyterian minister was forbidden, the exact conditions under which his first marriage had taken place.

The jury didn't accept his defense, and found him guilty. His sentence of transportation would leave 2 wives destitute. But his lawyer made a legal issue that should be heard separately. Presiding Judge Crampton ordered the issue to be heard at the Queen's Bench later in the year.

Presbyterians expected that the legal challenge would be dismissed, as such marriages had been taking place for generations. Still, John was following the subject closely. The Queen's Bench heard the case in Dublin on November 26, 1841. The arguments centered about precedents in Irish Common Law. Smith's lawyer argued that Common Law required couples to be married by someone in Holy Orders. No Presbyterian Minister held such elevated status, and therefore none had the right to perform marriages.

The Irish government assigned their leading law official to argue the case for the Crown. He argued that marriage was a civil contract under Common Law. Therefore, no minister of any kind was required. Whether or not the presiding clergyman had Holy Orders was therefore of no relevance.

The ten judges who heard the arguments took their time with the issue, so the decree wasn't issued until January 11, 1842. By a vote of 8 to 2, the judges voted that Presbyterian ministers had no right to perform a marriage where one of the participants was a member of the Church of Ireland. With that pronouncement, Smith became a free man, thousands of children born to these illegal marriages became bastards under the law. Men who believed themselves legitimately married could now abandon their wives. Settled inheritances could be claimed by others.

Presbyterians erupted in anger at this insult to their ministers who were now regarded merely as teachers, and to the insult to their religion. Meetings were immediately called at which resolutions making this fury very clear were voted and dispatched to Parliament. Uniformly, they demanded that Parliament undo the damage that had been done, and quickly too. For John, there was a personal element to the problem, as his Uncle James Harshaw had married Sarah Kidd, who was a member of the Church of Ireland. So their 10 children had become bastards too.

The new session of Parliament began on February 3rd with high Presbyterian expectations that Parliament would quickly vote to legalize the mixed marriages and validate the right of Presbyterian ministers to resume performing them. Daniel O'Connell raised the issue, pointing out all the legal problems that followed the decision.

Conservative Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel rose to speak. He assured Irish Presbyterians that he planned to introduce a bill that would remedy the problems. All existing marriages would soon be legal. However, he had yet to decide whether or not Presbyterian ministers would have their rights to marry mixed couples restored.

Local Presbyterians wanted their voices heard on this critical issue. A meeting of ministers and elders of local churches was held at the 1st Presbyterian Church in Newry to pass their own resolutions. John's uncle Harshaw was present and could provide a first hand account of what was said and done at the meeting. They demanded full marriage rights that extended into the future as well as correcting the threats to existing marriages. Rev. Mr. Weir, minister of the 1st Presbyterian Church, offered both appeal and veiled warning. "The link which the Presbyterians of Ulster formed in British connection-their well known respect for the laws, demanded and deserved this from the Government and Legislature of the Empire."

Corrective legislation was introduced in Parliament ot Thursday February 24th by Lord Eliot, the current Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. He claimed that Presbyterian marriages were performed in a "very irregular manner." There was no licence, no notice, and the ceremonies were often performed by "degraded ministers." This distressing situation would end with the passage of the legislation the Conservatives had written. All previously performed marriages would be recognized, but no more would be permitted. Though the Church of Ireland opposed even this moderate proposal, it quickly passed both Commons and Lords.

Presbyterians' religion had been denounced and degraded. They had no intention of acceding meekly to such an injustice. Rev. Henry Cooke, minister of the May Street Presbyterian Church in Belfast spoke for the offended religion. How dare Parliament remove rights that ministers had held for 200 years. How dare the Church of Ireland and its leaders in Parliament treat their ministers as mere teachers.

Rev. Cooke spoke to the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Belfast to amplify his objections. "It was necessary for the friends of Presbyterian honor and rights to stiffen the sinews of war, for they were employed in carrying on a great warfare. They were fighting for their ancient 'status' and for their precious priviledges and rights, civil and religious." These words reflected the spirit of the Ulster Presbyterians. Rev. Cooke expected that they would be sufficiently threatening to prompt Parliament to revisit the issue and undo the damage of the previous legislation.

There were other warnings as well, one from John's friend George Henderson, editor of the Newry Commercial Telegraph. "We tell them that they must promptly change their policy, else they will lose for ever the confidence of the Conservative party in this country and alienate the affections and sympathies of the best, the most orderly, the most loyal and the bravest of her Majesty's subjects-men who, should troublelous times arise, would stand side by side with England in the quarrel, and cheerfully face every danger, and peril life and limb in the maintenance of the Union."

Despite these strong words, the British government felt confident that Presbyterians would never align themselves with the Irish Catholics in opposition to Union with England. And in this supposition, they were right. No action was taken until 1844, and there was no Presbyterian revolt in Ireland. Rev. Cooke continued to talk to Prime Minister Peel, and helped work out the legislation that finally ended the dispute. Ministers would be able to perform mixed marriages but with restrictions that didn't apply to the clergy of the Church of Ireland, such as published notice of intent, and longer waiting periods. They would not be allowed to marry a Presbyterian to a Catholic. The bill passed in August 1844, but the hard feelings lasted much longer.

To John, this was just another example of the kind of legislation that the English inflicted on the Irish. Before the legislation passed, John had taken a step that changed the whole course of the rest of his life.

Sources: The Newry Commercial Telegraph; Hansard Parliamentary Debate; 1844 Marriage Act and Its Consequences: Political-Relgious Agitation and Its Consequences for Ulster Genealogy, Brian T. McClintock.

Every August, summer court sessions, Assizes, took place across Ireland. No one foresaw the problems that would flow from a minor court case in the Armagh Assizes. A rather uncouth man named Samuel Smith was on trial for bigamy. The facts seemed straight forward. He had married Jane Gordon from Portadown in 1839. Since he had had married another woman 8 years before, the court case seemed routine. And it was except for the unique defense Smith mounted. He claimed that his first marriage was illegal as he was a member of the Church of Ireland, and any marriage with a Presbyterian, performed by a Presbyterian minister was forbidden, the exact conditions under which his first marriage had taken place.

The jury didn't accept his defense, and found him guilty. His sentence of transportation would leave 2 wives destitute. But his lawyer made a legal issue that should be heard separately. Presiding Judge Crampton ordered the issue to be heard at the Queen's Bench later in the year.

Presbyterians expected that the legal challenge would be dismissed, as such marriages had been taking place for generations. Still, John was following the subject closely. The Queen's Bench heard the case in Dublin on November 26, 1841. The arguments centered about precedents in Irish Common Law. Smith's lawyer argued that Common Law required couples to be married by someone in Holy Orders. No Presbyterian Minister held such elevated status, and therefore none had the right to perform marriages.

The Irish government assigned their leading law official to argue the case for the Crown. He argued that marriage was a civil contract under Common Law. Therefore, no minister of any kind was required. Whether or not the presiding clergyman had Holy Orders was therefore of no relevance.

The ten judges who heard the arguments took their time with the issue, so the decree wasn't issued until January 11, 1842. By a vote of 8 to 2, the judges voted that Presbyterian ministers had no right to perform a marriage where one of the participants was a member of the Church of Ireland. With that pronouncement, Smith became a free man, thousands of children born to these illegal marriages became bastards under the law. Men who believed themselves legitimately married could now abandon their wives. Settled inheritances could be claimed by others.

Presbyterians erupted in anger at this insult to their ministers who were now regarded merely as teachers, and to the insult to their religion. Meetings were immediately called at which resolutions making this fury very clear were voted and dispatched to Parliament. Uniformly, they demanded that Parliament undo the damage that had been done, and quickly too. For John, there was a personal element to the problem, as his Uncle James Harshaw had married Sarah Kidd, who was a member of the Church of Ireland. So their 10 children had become bastards too.

The new session of Parliament began on February 3rd with high Presbyterian expectations that Parliament would quickly vote to legalize the mixed marriages and validate the right of Presbyterian ministers to resume performing them. Daniel O'Connell raised the issue, pointing out all the legal problems that followed the decision.

Conservative Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel rose to speak. He assured Irish Presbyterians that he planned to introduce a bill that would remedy the problems. All existing marriages would soon be legal. However, he had yet to decide whether or not Presbyterian ministers would have their rights to marry mixed couples restored.

Local Presbyterians wanted their voices heard on this critical issue. A meeting of ministers and elders of local churches was held at the 1st Presbyterian Church in Newry to pass their own resolutions. John's uncle Harshaw was present and could provide a first hand account of what was said and done at the meeting. They demanded full marriage rights that extended into the future as well as correcting the threats to existing marriages. Rev. Mr. Weir, minister of the 1st Presbyterian Church, offered both appeal and veiled warning. "The link which the Presbyterians of Ulster formed in British connection-their well known respect for the laws, demanded and deserved this from the Government and Legislature of the Empire."

|

| Sandys Street Presbyterian Church |

Corrective legislation was introduced in Parliament ot Thursday February 24th by Lord Eliot, the current Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. He claimed that Presbyterian marriages were performed in a "very irregular manner." There was no licence, no notice, and the ceremonies were often performed by "degraded ministers." This distressing situation would end with the passage of the legislation the Conservatives had written. All previously performed marriages would be recognized, but no more would be permitted. Though the Church of Ireland opposed even this moderate proposal, it quickly passed both Commons and Lords.

Presbyterians' religion had been denounced and degraded. They had no intention of acceding meekly to such an injustice. Rev. Henry Cooke, minister of the May Street Presbyterian Church in Belfast spoke for the offended religion. How dare Parliament remove rights that ministers had held for 200 years. How dare the Church of Ireland and its leaders in Parliament treat their ministers as mere teachers.

Rev. Cooke spoke to the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Belfast to amplify his objections. "It was necessary for the friends of Presbyterian honor and rights to stiffen the sinews of war, for they were employed in carrying on a great warfare. They were fighting for their ancient 'status' and for their precious priviledges and rights, civil and religious." These words reflected the spirit of the Ulster Presbyterians. Rev. Cooke expected that they would be sufficiently threatening to prompt Parliament to revisit the issue and undo the damage of the previous legislation.

There were other warnings as well, one from John's friend George Henderson, editor of the Newry Commercial Telegraph. "We tell them that they must promptly change their policy, else they will lose for ever the confidence of the Conservative party in this country and alienate the affections and sympathies of the best, the most orderly, the most loyal and the bravest of her Majesty's subjects-men who, should troublelous times arise, would stand side by side with England in the quarrel, and cheerfully face every danger, and peril life and limb in the maintenance of the Union."

Despite these strong words, the British government felt confident that Presbyterians would never align themselves with the Irish Catholics in opposition to Union with England. And in this supposition, they were right. No action was taken until 1844, and there was no Presbyterian revolt in Ireland. Rev. Cooke continued to talk to Prime Minister Peel, and helped work out the legislation that finally ended the dispute. Ministers would be able to perform mixed marriages but with restrictions that didn't apply to the clergy of the Church of Ireland, such as published notice of intent, and longer waiting periods. They would not be allowed to marry a Presbyterian to a Catholic. The bill passed in August 1844, but the hard feelings lasted much longer.

|

| Robert Peel |

To John, this was just another example of the kind of legislation that the English inflicted on the Irish. Before the legislation passed, John had taken a step that changed the whole course of the rest of his life.

Sources: The Newry Commercial Telegraph; Hansard Parliamentary Debate; 1844 Marriage Act and Its Consequences: Political-Relgious Agitation and Its Consequences for Ulster Genealogy, Brian T. McClintock.

Thursday, September 8, 2011

Death In Ballyroney

|

| Daniel O'Connell (Wikpedia.org) |

On Christmas Day of 1841, an event took place a short distance each of John's home in Loughorne that would take him a step closer to a life in politics. This was one of the few days of rest for Irish farmers and they made the most of the holiday. One group of men had gathered for a horse race in the townland of Ballyroney. Not far away, a group of young Protestants had gathered together to shoot off their guns. This was an opportunity to show off their firepower to the local Catholics who were not allowed to have guns.

View Beloved Politician Map in a larger map

When these separate activities were over, each group hurried to their favorite pubs. The racing fans gathered at a pub owned by John Copes. The shooters were about a mile away at a pub owned by a man named Green. The drinkers at Copes Pub were a mix of Catholic and Protestant. And about 4 PM, as the lanterns were lit, a fight broke out between a Catholic named McKeown, and a Protestant named McRoberts. With the help of a powerful Catholic farmer, Hugh McArdle, Mr. Copes was able to stop the fight quickly and restore order. Lawrence McKeown was ejected and peace restored.

Unfortunately, Thomas Scott witnessed the start of the fight, and raced away to Green's Pub for reinforcements without witnessing the quick end to the ruckus. A few minutes later, Mr. Copes was standing at the door of his pub, when he saw the Protestant boys running in his direction. He hurried inside in an effort to bar the door, but the angry mob, led by Thomas Scott and his friends William Andrews and William Stewart were not to be deterred.

The mob battered the door open, and rushed in, demanding that McKeown be turned over to them. When Copes told them that all was well, and that McKeown had been sent home, they should have left peaceably. But instead they began fighting with everyone in the pub, and seemed to have a special interest in attacking Hugh McArdle.

Realizing what was happening, Hugh fled from the pub, and took shelter in the home of friends. There were 4 witnesses to what happened next, the owner Peter Ward, his wife and daughter, and Hugh's son Arthur. The only weapon they had to defend themselves against the armed mob who followed him there was a dung fork, known as a grape.

The terrified occupants had no time to prepare before the door burst open and the mob rushed inside. They grabbed the grape from Arthur, and used it to knock Hugh senseless. They dragged Hugh outside, and a second later, someone fired a gun.

As the sounds of the mob faded, the survivors cautiously opened the door and peered out. Hugh lay dead on the ground just outside the door. He had been shot once in the chest at such a close range that his shirt was on fire.

There was no secret as to the identity of the perpetrators. They were all local residents well known to all the witnesses. The men who had rioted at Copes Pub and then trailed and murdered Hugh were arrested and held at Downpatrick Jail for trial to be held in February 1842.

This murder brought to mind the murder of Samuel Duncan on Rathfriland Road. Then it was a Protestant murdered by Catholics. Though identification was suspect, five Catholics were hung for the crime, and 2 more transported for life. This time, the victim was a Catholic, the murders Protestant. John Martin was far from the only neighbor who wondered whether or not with the situation now reversed if justice would be done.

The doubt as to whether a Protestant jury would convict McArdle's killers was expressed by the editor of a Belfast newspaper, Charles Gavin Duffy, who would later become one of John's good friends. "It is a fact, which would fill Englishmen with amazement and horror, that a vast proportion of the people of Down, while they have no reason to doubt the guilt of the prisoners, for the murder of McArdle, are perfectly confident that they will escape all punishment. This belief is shared by Protestants and Catholics alike, and depends upon the assumption that an Orange Jury will acquit them, though their guilt be as certain as a mathematical demonstration. The state of public feeling, where the people are exposed to the fury of the assassination on one side, and the perjury of the partisan Juror on the other, may be conceived."

The trial began on February 28th, with William Mathews, William Andrews, William Stewart and Thomas Scott all charged with murder. Jury selection was all important, and immediately a legal trick prevented any challenges of the jury. At the last minute, a different trial was scheduled and jury panel seated. Then the defendant was released, but the jury was carried over to the McArdle trial. As it was already empaneled, no challenges were allowed.

When the evidence had been presented, Judge Crampton recounted the testimony and the strength of it. "in my opinion I can't understand the crime as amounting to anything short of murder...If you believe the evidence for the Crown, especially that of Peter Ward, no doubt that the four, or three at least, of the prisoners are guilty of the crime laid in the indictment."

Such a strong statement from the judge brought some hope to the Catholic community that there would be justice for Hugh McArdle and for them. The jury deliberated for less than an hour and returned a verdict of "Not Guilty."

Though the verdict was expected, it was still a shock to those in the Courthouse. Judge Cramption ordered the Court to be immediately cleared. The crowd of angry Catholics and triumphant Protestants rushed outside to continue their battles on the Courthouse steps and down the hill. Sadly, Catholics learned once again that there would be no justice for them under English law. Protestants learned that they could look to English law and the English government as their protectors no matter what they chose to do.

Even members of Parliament were surprised and concerned about the issue of justice in Ireland. A major debate on the general subject of justice in Ireland. R. L. Sheil, an Irish member, stated the case. "I am well aware that English gentlemen feel some surprise at the constant complaints which are made by Roman Catholics that in the north of Ireland juries are almost exclusively composed of Protestants, and that we should attach importance to the religion of those who are to arbitrate upon our lives."

In the government response, Lord Robert Peel, who was the Conservative Prime Minister, avoided the issue of the McArdle murder, instead focusing on the fairness of the Englishmen who were in charge of Ireland and its legal system. No action was taken to make the jury system of Ireland a fair one. By the time John Martin first faced an Irish jury a few years later, nothing had been done to improve Irish juries.

Sources: The Newry Commercial Telegraph, January 1, 1842 to April 7, 1842; Debates in Parliament, Hansard, July 18, 1842.

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Washington DC 1840

Washington was already becoming uncomfortably warm for an Irishman when John Martin arrived there toward the end of April, 1840. He found American heat drained him of energy, but it didn't trigger any of his dreaded asthma attacks.

The American capital city was very primitive when compared to the capitals in Ireland and England. The city was laid out in the grid pattern that was created when the city was originally planned. But many of the streets were dry, rutted paths, dividing one empty blocks from another. The Capital building and White House were in place. Here and there were nice residences and boarding houses for use of important officials and members of Congress. Even then, government was the business of the city and those who lived there.

For the first time, John had entered a place where slavery was legal. It must have been very upsetting to such a kind hearted man to see men in chains, herded along Pennsylvania Ave toward the slave auctions that were held in Alexandria.

While slaves were waiting for the next auction, they were held in prison-like structures known as slave pens. There were several of them at that time, but the most notorious one was the Robey Slave Pen. How could such a dreadful place be located on the Mall, along Independence Ave, just beyond the shadows of the Capital itself?

John certainly passed the slave pen, while he walked around the city. The pen consisted of a wooden building which was surrounded by a 14 foot wooden palisade. Only a small part of the interior prison extended above the wall. There was one square cut into the walls, through which John could see the faces of the black men and women imprisoned inside. There was no glass over the opening, so heat and hordes of buzzing and biting insects had easy access to torment the prisoners inside. In the winter, prisoners actually froze to death. And nothing blocked the terrible stench that reached all those who walked passed. John certainly noticed similarities to the hovels of Ireland in which his poorest neighbors lived.

Visitors to Washington usually stopped by the Capital to watch Congress if it was in session. With John's experiences with life under foreign rule, he would certainly have been interested in observing a government run by its own citizens. It was just what he hoped would exist for Ireland one day.

The building itself had a certain grandeur about it. The impressive front stairs led to a grand central hall decorated with heroic paintings. Doors on either side led to the two chambers of government. The Senate met in a small room to the right of the main hall. Still it was sufficiently large for the 56 members currently representing 28 states. It was constructed in the shape of a semi-circle with the seat for the presiding officer raised about the senators and artistically decorated with lush draperies.

The visitors' gallery followed the curve of the room and gave visitors an intimate view of proceedings taking place just a few feet below them. John was not present when great debates were taking place there. But he was able to see at one time three of the most able Senators to ever serve the United States, Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun and Daniel Webster. These men were already well known, and John would have appreciated the honor of seeing them in one place at the same time.

The situation in the House of Representatives was quite different. Though the room was shaped like the Senate, it was much larger in size. The Speaker's chair was located above the floor and draped to match the presiding officer of the Senate. Pillars on either side of the Speaker's chair decorated the large blank wall. Each member had his own desk and leather chair, all of which were arranged across the floor in pie-shaped wedges.

Visitors were seated in a gallery which followed the circumference of the room. But the size of the chamber and the distance from the front of the hall made it often difficult for visitors to understand what was going on during debates. In this room, members behaved very differently from the Senate. Many of the men who had been elected sought office for personal gain rather than public service. They sought to make debate and the making of laws so unpleasant that men of quality and desire to serve their country would not risk running for office. Many of them had taken up the habit of chewing tobacco while the House was in session. Though spittoons were provided, members preferred to spit upon the floor.

Shortly after John arrived in Washington, conduct in the House descended to a rare low. On April 21st, the House was in session when a Jacksonian Democrat from North Carolina named Jesse Bynum got up from his seat, crossed the floor and began beating a Whig member from Louisiana named Rice Garland. Officials and other members intervened, so Garland wasn't greatly injured. Both members were temporarily removed, and an investigation was begun. The reason for the attack wasn't clear, perhaps nothing more than short tempers and differences between political parties. Garland soon resigned to become a judge in Louisiana.

This experience in Democracy couldn't have been comforting to John. He certainly knew of Irish leaders who would behave no differently, if Ireland had its own government. But he took hope that wise men would step forward to lead there as they had in the Senate.

Sources: American Notes, by Charles Dickens; C-Spanhome@2000; A Century of Lawmaking for a New nation. U. S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875; http://www.lib.unc.edu/; www.terrain.org/albumns/23/savoy.htm: Retrospect of Western Travel (1838) Harriet Martineau; Edward S. Abdy, Journal of a Residence and Tour of the United States, (3vols. London 1835); Dr. Hyde Salter, Asthma.

The American capital city was very primitive when compared to the capitals in Ireland and England. The city was laid out in the grid pattern that was created when the city was originally planned. But many of the streets were dry, rutted paths, dividing one empty blocks from another. The Capital building and White House were in place. Here and there were nice residences and boarding houses for use of important officials and members of Congress. Even then, government was the business of the city and those who lived there.

|

| Washington Landscape in 1846 Looking West |

For the first time, John had entered a place where slavery was legal. It must have been very upsetting to such a kind hearted man to see men in chains, herded along Pennsylvania Ave toward the slave auctions that were held in Alexandria.

While slaves were waiting for the next auction, they were held in prison-like structures known as slave pens. There were several of them at that time, but the most notorious one was the Robey Slave Pen. How could such a dreadful place be located on the Mall, along Independence Ave, just beyond the shadows of the Capital itself?

John certainly passed the slave pen, while he walked around the city. The pen consisted of a wooden building which was surrounded by a 14 foot wooden palisade. Only a small part of the interior prison extended above the wall. There was one square cut into the walls, through which John could see the faces of the black men and women imprisoned inside. There was no glass over the opening, so heat and hordes of buzzing and biting insects had easy access to torment the prisoners inside. In the winter, prisoners actually froze to death. And nothing blocked the terrible stench that reached all those who walked passed. John certainly noticed similarities to the hovels of Ireland in which his poorest neighbors lived.

Visitors to Washington usually stopped by the Capital to watch Congress if it was in session. With John's experiences with life under foreign rule, he would certainly have been interested in observing a government run by its own citizens. It was just what he hoped would exist for Ireland one day.

The building itself had a certain grandeur about it. The impressive front stairs led to a grand central hall decorated with heroic paintings. Doors on either side led to the two chambers of government. The Senate met in a small room to the right of the main hall. Still it was sufficiently large for the 56 members currently representing 28 states. It was constructed in the shape of a semi-circle with the seat for the presiding officer raised about the senators and artistically decorated with lush draperies.

The visitors' gallery followed the curve of the room and gave visitors an intimate view of proceedings taking place just a few feet below them. John was not present when great debates were taking place there. But he was able to see at one time three of the most able Senators to ever serve the United States, Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun and Daniel Webster. These men were already well known, and John would have appreciated the honor of seeing them in one place at the same time.

|

| US Senate during a later (1850) debate |

The situation in the House of Representatives was quite different. Though the room was shaped like the Senate, it was much larger in size. The Speaker's chair was located above the floor and draped to match the presiding officer of the Senate. Pillars on either side of the Speaker's chair decorated the large blank wall. Each member had his own desk and leather chair, all of which were arranged across the floor in pie-shaped wedges.

Visitors were seated in a gallery which followed the circumference of the room. But the size of the chamber and the distance from the front of the hall made it often difficult for visitors to understand what was going on during debates. In this room, members behaved very differently from the Senate. Many of the men who had been elected sought office for personal gain rather than public service. They sought to make debate and the making of laws so unpleasant that men of quality and desire to serve their country would not risk running for office. Many of them had taken up the habit of chewing tobacco while the House was in session. Though spittoons were provided, members preferred to spit upon the floor.

Shortly after John arrived in Washington, conduct in the House descended to a rare low. On April 21st, the House was in session when a Jacksonian Democrat from North Carolina named Jesse Bynum got up from his seat, crossed the floor and began beating a Whig member from Louisiana named Rice Garland. Officials and other members intervened, so Garland wasn't greatly injured. Both members were temporarily removed, and an investigation was begun. The reason for the attack wasn't clear, perhaps nothing more than short tempers and differences between political parties. Garland soon resigned to become a judge in Louisiana.

This experience in Democracy couldn't have been comforting to John. He certainly knew of Irish leaders who would behave no differently, if Ireland had its own government. But he took hope that wise men would step forward to lead there as they had in the Senate.

Sources: American Notes, by Charles Dickens; C-Spanhome@2000; A Century of Lawmaking for a New nation. U. S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875; http://www.lib.unc.edu/; www.terrain.org/albumns/23/savoy.htm: Retrospect of Western Travel (1838) Harriet Martineau; Edward S. Abdy, Journal of a Residence and Tour of the United States, (3vols. London 1835); Dr. Hyde Salter, Asthma.

Monday, July 18, 2011

New York City 1839

John Martin was an observant traveler, and found much to interest him that others might have passed by without seeing. As the Great Western docked on the East River, he could see a section of grand stone buildings. These newly constructed buildings marked the area of the city which had been destroyed by a dreadful fire that took place in 1835. It began in a single building at the corner of Pearl and Exchange Streets on a bitterly cold December night. The temperature stood at 17 degrees below zero. The usual water sources, wells and reservoirs, and the East River, were frozen and useless. The fire roared unchecked through the lower part of Manhattan.

In the four years since the fire, the area had been rebuilt with more fire resistant buildings. In addition, a great new water source, the Croton Water System, had been planned and construction was already underway. It would bring water from upstate New York by way of a great aqueduct. The cities of Ireland were always in similar danger from fire. So John was certainly interested in this grand solution to a universal problem.

There were several comfortable hotels for John to choose from, most sprinkled along Broadway. From that central location, John could easily walk about most of the city. New York was laid out in a grid pattern that made exploration easy. As soon as John had established himself in his hotel, he was out to explore, and observe.

Broadway was bustling with pedestrians and vehicles of all sorts. Evidences of wealth were easily visible in the brightly colored and elegant clothes of pedestrians, and ornate coaches often driven by black men in uniforms designed to impress. But John saw other signs of the first great depression which had occurred two years before. President Andrew Jackson had refused to re-charter the Second Bank of the United States. This resulted in a sharp rise in inflation, which rapidly reduced the value of paper money. Government land sales stopped because of uncertainty about the value of money used to purchase the land. On May 10, 1837, all the banks of New York refused to deal in paper money at all, accepting deposits of gold and silver only. The economy collapsed just as the term of the new president Martin Van Buren began.

The economy had begun to recover as John took his first walk around the city. Still, the city was dirty, beggars held out their caps to passersby, the stench of garbage fouled the air once visitors left the glitz of Broadway. John certainly thought of how like his home town of Newry this proud city of the new world seemed

John was certainly had a special interest in the Irish newcomers to the city and how they were being received in their new homeland. Irish immigrants were easily visible, at least the ones who came without funds and had yet to find work. The old fashioned jackets, trousers and hats made them stand out on any street, just as if they had had a large identifying sign attached to their backs. John could easily see the scornful looks of New Yorkers and hear the taunts that were shouted after them. Irish women often found work as maids in the grand houses of the city. So a servant's uniform produced the same scorn as Irish hats.

Most of the Irish immigrants lived in an area of the city called Five Points, its name coming from the intersection of several streets in one place. John certainly walked down to visit the area. The wooden tenements were crammed beyond capacity with Irish immigrants. Sewerage ran freely along streets and alleys, contaminating water and breeding disease. The great cholera epidemic roared out of Five Points and across the city in 1831. John found the new lives of his fellow Irishmen saddening. The immigrants had sacrificed so much and found so little. Their dreams of a better life were quickly dashed. Now they would live out their lives far from the green fields and fresh air of their native land, never to see their families and friends again.

Not surprisingly, there was much desperation in the Five Points and much crime. Clearly, a new prison in the area was a prime necessity. So a large prison was built the year before John visited. It was designed to look like an Egyptian tomb, hence the name by which it was known. Irish suspects were taken from the streets and slums of Five Points in the black paddy wagons into the dark cells of the tombs. Just the sight of this grim and aptly named building must have depressed. Fortunately, John had no way of knowing that just 10 years later, he would enter a similar prison as a convicted felon himself.

A few of the immigrant Irish achieved great success. One of them was a cook named William Niblo. After some years in New York, he was able to open one of the first restaurants in the city, Niblo Garden, located at Broadway and Prince Street. The inside of the restaurant was decorated with shrubs, and trees. Birds sung from their cages. This business opened shortly before John arrived, and was already wildly successful. John certainly heard about this Irish success story and must have dined there at least once.

There was one story that occupied the attention of New Yorkers when John arrived. Just a few days earlier, a strange, dark ship had been spotted off the shores of New York. Reports of its presence came from crews of tugs and small ships passing in the same area. On the 26th of August, Thomas Gedney of the USS Washington located the ship Amistad off Long Island, seized it, and brought it to New Haven. The ship was controlled by 54 slaves.

A hearing was held before the slaves were brought ashore in an effort to keep them in custody for return to their owners in Havana. However, the hearing judge decided to hold them for trial and put them in jail on American soil. When John arrived in New York, newspapers were still putting the latest Amistad news on the front pages of their papers.. So great was the interest in the story that a play called "Long Low Black Schooner" had opened in the Bowery Theater a week earlier

The accounts of events were unique and riveting, arousing intense and opposing emotions, according to views on slavery. These slaves had been captured in Africa and sold in the spring of 1839, though transportation of slaves across the ocean had been made illegal. In Havana, they had been sold to work in the sugar cane fields. They were put on board the Armistad for the short trip from the slave market to the cane fields.

One of the slaves Joseph Cinque, a man with training in working metals, was able to free himself and the other slaves. After a fierce battle during which the Captain and 2 slaves were killed, the slaves succeeded in capturing the ship. They intended to sail the ship back to Africa. Lacking any familiarity with navigation, they spared Jose Ruiz and Pedro Montez who promised to steer them home to Africa.But the two men had no intention of doing that. They sailed the ship eastward by day and northward by night. This deception brought them off the coast where the slaves could be recaptured.

Abolitionists hurried to help raise funds to ensure that the men who risked their lives to fight for their freedom would indeed be freed. The first hearings had not been held when John left New York to visit his sister Jane in Canada. However, by the time he returned to New York to leave for home, the slaves had been ordered freed and returned to their homes in Sierra Leone. They settled in Farmington CN while the case was appealed. In 1842, the Supreme Court concurred in the lower court decision. Cinque and his companions returned to Africa, free men again.

Sources. "Asthma" by Dr. Hyde Salter. "Journal of Philip Hone," by Philip Hone. "Recession of 1837," Wikipedia. "Five Points," by Wikipedia. "Fire of 1835," Wikipedia. "Gastropolis: Food and New York City," by Hannah Lawson. "Journal of a Tour of New York In the Year 1830" by John Fowler. "American Notes," by Charles Dickens. "Retrospect of Western Travel," by Harriet Martineau.

In the four years since the fire, the area had been rebuilt with more fire resistant buildings. In addition, a great new water source, the Croton Water System, had been planned and construction was already underway. It would bring water from upstate New York by way of a great aqueduct. The cities of Ireland were always in similar danger from fire. So John was certainly interested in this grand solution to a universal problem.

There were several comfortable hotels for John to choose from, most sprinkled along Broadway. From that central location, John could easily walk about most of the city. New York was laid out in a grid pattern that made exploration easy. As soon as John had established himself in his hotel, he was out to explore, and observe.

Broadway was bustling with pedestrians and vehicles of all sorts. Evidences of wealth were easily visible in the brightly colored and elegant clothes of pedestrians, and ornate coaches often driven by black men in uniforms designed to impress. But John saw other signs of the first great depression which had occurred two years before. President Andrew Jackson had refused to re-charter the Second Bank of the United States. This resulted in a sharp rise in inflation, which rapidly reduced the value of paper money. Government land sales stopped because of uncertainty about the value of money used to purchase the land. On May 10, 1837, all the banks of New York refused to deal in paper money at all, accepting deposits of gold and silver only. The economy collapsed just as the term of the new president Martin Van Buren began.

The economy had begun to recover as John took his first walk around the city. Still, the city was dirty, beggars held out their caps to passersby, the stench of garbage fouled the air once visitors left the glitz of Broadway. John certainly thought of how like his home town of Newry this proud city of the new world seemed

John was certainly had a special interest in the Irish newcomers to the city and how they were being received in their new homeland. Irish immigrants were easily visible, at least the ones who came without funds and had yet to find work. The old fashioned jackets, trousers and hats made them stand out on any street, just as if they had had a large identifying sign attached to their backs. John could easily see the scornful looks of New Yorkers and hear the taunts that were shouted after them. Irish women often found work as maids in the grand houses of the city. So a servant's uniform produced the same scorn as Irish hats.

Most of the Irish immigrants lived in an area of the city called Five Points, its name coming from the intersection of several streets in one place. John certainly walked down to visit the area. The wooden tenements were crammed beyond capacity with Irish immigrants. Sewerage ran freely along streets and alleys, contaminating water and breeding disease. The great cholera epidemic roared out of Five Points and across the city in 1831. John found the new lives of his fellow Irishmen saddening. The immigrants had sacrificed so much and found so little. Their dreams of a better life were quickly dashed. Now they would live out their lives far from the green fields and fresh air of their native land, never to see their families and friends again.

Not surprisingly, there was much desperation in the Five Points and much crime. Clearly, a new prison in the area was a prime necessity. So a large prison was built the year before John visited. It was designed to look like an Egyptian tomb, hence the name by which it was known. Irish suspects were taken from the streets and slums of Five Points in the black paddy wagons into the dark cells of the tombs. Just the sight of this grim and aptly named building must have depressed. Fortunately, John had no way of knowing that just 10 years later, he would enter a similar prison as a convicted felon himself.

A few of the immigrant Irish achieved great success. One of them was a cook named William Niblo. After some years in New York, he was able to open one of the first restaurants in the city, Niblo Garden, located at Broadway and Prince Street. The inside of the restaurant was decorated with shrubs, and trees. Birds sung from their cages. This business opened shortly before John arrived, and was already wildly successful. John certainly heard about this Irish success story and must have dined there at least once.

There was one story that occupied the attention of New Yorkers when John arrived. Just a few days earlier, a strange, dark ship had been spotted off the shores of New York. Reports of its presence came from crews of tugs and small ships passing in the same area. On the 26th of August, Thomas Gedney of the USS Washington located the ship Amistad off Long Island, seized it, and brought it to New Haven. The ship was controlled by 54 slaves.

A hearing was held before the slaves were brought ashore in an effort to keep them in custody for return to their owners in Havana. However, the hearing judge decided to hold them for trial and put them in jail on American soil. When John arrived in New York, newspapers were still putting the latest Amistad news on the front pages of their papers.. So great was the interest in the story that a play called "Long Low Black Schooner" had opened in the Bowery Theater a week earlier

The accounts of events were unique and riveting, arousing intense and opposing emotions, according to views on slavery. These slaves had been captured in Africa and sold in the spring of 1839, though transportation of slaves across the ocean had been made illegal. In Havana, they had been sold to work in the sugar cane fields. They were put on board the Armistad for the short trip from the slave market to the cane fields.

One of the slaves Joseph Cinque, a man with training in working metals, was able to free himself and the other slaves. After a fierce battle during which the Captain and 2 slaves were killed, the slaves succeeded in capturing the ship. They intended to sail the ship back to Africa. Lacking any familiarity with navigation, they spared Jose Ruiz and Pedro Montez who promised to steer them home to Africa.But the two men had no intention of doing that. They sailed the ship eastward by day and northward by night. This deception brought them off the coast where the slaves could be recaptured.

Abolitionists hurried to help raise funds to ensure that the men who risked their lives to fight for their freedom would indeed be freed. The first hearings had not been held when John left New York to visit his sister Jane in Canada. However, by the time he returned to New York to leave for home, the slaves had been ordered freed and returned to their homes in Sierra Leone. They settled in Farmington CN while the case was appealed. In 1842, the Supreme Court concurred in the lower court decision. Cinque and his companions returned to Africa, free men again.

Sources. "Asthma" by Dr. Hyde Salter. "Journal of Philip Hone," by Philip Hone. "Recession of 1837," Wikipedia. "Five Points," by Wikipedia. "Fire of 1835," Wikipedia. "Gastropolis: Food and New York City," by Hannah Lawson. "Journal of a Tour of New York In the Year 1830" by John Fowler. "American Notes," by Charles Dickens. "Retrospect of Western Travel," by Harriet Martineau.

Monday, June 27, 2011

Visiting the US and Canada 1839 - 1840

Author's note. Travel at this period was long, difficult and sometimes even dangerous. Still, John Martin decided to take an extended trip to the United States and Canada. This post will follow John, as he traveled by various means for almost a year. This will be followed by companion posts describing in greater detail what he experienced in New York City, and Washington DC.

By the summer of 1839, John Martin, had settled into the life and responsibilities of an Irish landlord. He was, by then, 27 years old, with time and money to travel. He had already spent a number of weeks in London, But he felt it was time to take a longer trip, this time to the US and Canada. The main reason behind this choice was to visit to his older sister Jane who had emigrated to Canada in 1833 with her husband Donald Fraser and their children. But he had a great interest in seeing new places, and learning new things as well.

So, in August of that year, John took the steamer across the Irish Sea to England and on to Bristol. There he had booked passage on a strange new kind of hybrid ship, part sailing ship, part paddle-wheeled steamer, the Great Western. This ship was the finest and fastest ship then crossing the ocean, getting from Bristol to New York City in just 16 days.

The ocean was very rough for much of the trip, "boistrous" as John described it. John was listed in the ship's manifest as a merchant as were a substantial number of the other 100 passengers. Some were families with children and servants. The 24 staterooms for passengers surrounded a luxurious main salon. The sleeping spaces were not to John's liking. He needed fresh air. And there he was, shut into an airless space, surrounded by seasick companions. John was a fine sailor, never enduring a moment of seasickness. Fortunately, the wretched conditions caused no problem with asthma.

Gulls provided the first warning that land was not far beyond the horizon. Other ships that clung to the coastline began to appear. John was on deck to watch the islands of the narrows grow distinct before his eyes. Beyond this constricted passageway, New York Harbor and the great city opened up before him. The Great Western always seemed to attract attention, so there was a convoy of other ships as the Western moved into the harbor and up the East River where it docked. The trip across the Atlantic had taken just 16 days,

John had a grand plan for his trip. First he spent a week in New York City, before embarking on a steamer which transported him up the Hudson River past the great palisades, and West Point to Albany. From there he switched to train travel. Trains in those days were segregated by gender, the cars rather resembling shabby buses of today. He crossed Lake Ontario on a steamer headed to Hamilton Canada.

The trip from Hamilton to London Ontario was the worst of his trip. He traveled by carriage, one without springs, across about 80 miles of corduroy roads to reach London. John described the trip as "ordinary rack practice in the dungeons of the Inquisition." His agony finally ended at the log cabin where his sister lived in the woods of Upper Canada. Almost immediately, John suffered the worst asthma attack of his life. Fortunately, Jane well knew just what to do. When that had passed, John had no more asthma episodes on his entire trip.

Jane and her husband Donald lived in a small cabin on 200 acres of land in the Westminster section of London, land which they actually owned. This was small enough space for the Fraser's growing family. By the time John arrived, there were 4 children, and Jane was pregnant with her fifth child. But the family happily made room for their special visitor. The weather that fall was remarkably fine, "the temperature was deliciously mild, the air calm and dry; the sunlight, coming from a cloudless sky, was tempered by the peculiar dry haze of that season; there was neither rain, nor fog, nor damp of any kind. It was a luxury to me to breathe, the air felt so pure and light, and my lungs in such fine working order."

John even enjoyed his first real winter. The snow began in mid December, the storms followed by clear, sparkling frosty days. There was plenty enough time to discuss local revolutionary ideas. The value of land in London was being adversely affected when the English government set aside large tracts of land to support the local Anglican ministers. In early March, spring brought alternative periods of "thaw and frost." "At last, the spring suddenly appeared one lovely morning, with newly arrived singing-birds in her train."

When the ice on the Great Lakes broke, John left his family and the little cabin to continue his travels. He traveled across Ontario and Lake Erie to the St. Lawrence. He visited Montreal where the French residents had rebelled against the English government. Then he headed south to the United States, taking a steamer across Lake Champlain, and back again to New York, Philadelphia, and finally Washington DC. As John moved south and spring moved toward summer, he found the heat and humidity almost unbearable, hotter than any weather he had even experienced. He found it made him feel feverish, but he suffered no problems with his asthma.

From Washington, he crossed the Allegheny Mountains by train to Pittsburgh. There he could visit the Harshaw family, his mother's first cousins who had left Ballydoghtery and Warrenpoint a few years before. He viewed first hand American farms which his cousins, so impoverished in Ireland, now owned for themselves. His cousin Michael Harshaw lived in Pittsburgh where he was studying to be a Presbyterian Minister, something a poor boy without education could never do in Ireland.

He finished his circular trip by travelling from Pittsburgh to Cleveland, where he again traveled by lake steamers to Detroit and then back again to see his sister one more time. In the middle of the summer, he returned to New York City, and took the Great Western back to England. He had seen and learned much on this long trip, things that helped form the political ideas that governed much of the rest of his life.

View John Martin in America in a larger map

Sources: Dr. Hyde Salter, Asthma; Philip Hone's Diary; Dickens American Notes: P. A. Sillard, Life of John Martin.; Great Western background

By the summer of 1839, John Martin, had settled into the life and responsibilities of an Irish landlord. He was, by then, 27 years old, with time and money to travel. He had already spent a number of weeks in London, But he felt it was time to take a longer trip, this time to the US and Canada. The main reason behind this choice was to visit to his older sister Jane who had emigrated to Canada in 1833 with her husband Donald Fraser and their children. But he had a great interest in seeing new places, and learning new things as well.

So, in August of that year, John took the steamer across the Irish Sea to England and on to Bristol. There he had booked passage on a strange new kind of hybrid ship, part sailing ship, part paddle-wheeled steamer, the Great Western. This ship was the finest and fastest ship then crossing the ocean, getting from Bristol to New York City in just 16 days.

The ocean was very rough for much of the trip, "boistrous" as John described it. John was listed in the ship's manifest as a merchant as were a substantial number of the other 100 passengers. Some were families with children and servants. The 24 staterooms for passengers surrounded a luxurious main salon. The sleeping spaces were not to John's liking. He needed fresh air. And there he was, shut into an airless space, surrounded by seasick companions. John was a fine sailor, never enduring a moment of seasickness. Fortunately, the wretched conditions caused no problem with asthma.

| |

| Great Western on Maiden Voyage (public domain image) |

Gulls provided the first warning that land was not far beyond the horizon. Other ships that clung to the coastline began to appear. John was on deck to watch the islands of the narrows grow distinct before his eyes. Beyond this constricted passageway, New York Harbor and the great city opened up before him. The Great Western always seemed to attract attention, so there was a convoy of other ships as the Western moved into the harbor and up the East River where it docked. The trip across the Atlantic had taken just 16 days,

John had a grand plan for his trip. First he spent a week in New York City, before embarking on a steamer which transported him up the Hudson River past the great palisades, and West Point to Albany. From there he switched to train travel. Trains in those days were segregated by gender, the cars rather resembling shabby buses of today. He crossed Lake Ontario on a steamer headed to Hamilton Canada.

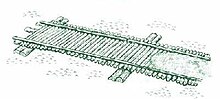

The trip from Hamilton to London Ontario was the worst of his trip. He traveled by carriage, one without springs, across about 80 miles of corduroy roads to reach London. John described the trip as "ordinary rack practice in the dungeons of the Inquisition." His agony finally ended at the log cabin where his sister lived in the woods of Upper Canada. Almost immediately, John suffered the worst asthma attack of his life. Fortunately, Jane well knew just what to do. When that had passed, John had no more asthma episodes on his entire trip.

|

| Corduroy road ( Wikipedia) |

Jane and her husband Donald lived in a small cabin on 200 acres of land in the Westminster section of London, land which they actually owned. This was small enough space for the Fraser's growing family. By the time John arrived, there were 4 children, and Jane was pregnant with her fifth child. But the family happily made room for their special visitor. The weather that fall was remarkably fine, "the temperature was deliciously mild, the air calm and dry; the sunlight, coming from a cloudless sky, was tempered by the peculiar dry haze of that season; there was neither rain, nor fog, nor damp of any kind. It was a luxury to me to breathe, the air felt so pure and light, and my lungs in such fine working order."

John even enjoyed his first real winter. The snow began in mid December, the storms followed by clear, sparkling frosty days. There was plenty enough time to discuss local revolutionary ideas. The value of land in London was being adversely affected when the English government set aside large tracts of land to support the local Anglican ministers. In early March, spring brought alternative periods of "thaw and frost." "At last, the spring suddenly appeared one lovely morning, with newly arrived singing-birds in her train."

When the ice on the Great Lakes broke, John left his family and the little cabin to continue his travels. He traveled across Ontario and Lake Erie to the St. Lawrence. He visited Montreal where the French residents had rebelled against the English government. Then he headed south to the United States, taking a steamer across Lake Champlain, and back again to New York, Philadelphia, and finally Washington DC. As John moved south and spring moved toward summer, he found the heat and humidity almost unbearable, hotter than any weather he had even experienced. He found it made him feel feverish, but he suffered no problems with his asthma.

From Washington, he crossed the Allegheny Mountains by train to Pittsburgh. There he could visit the Harshaw family, his mother's first cousins who had left Ballydoghtery and Warrenpoint a few years before. He viewed first hand American farms which his cousins, so impoverished in Ireland, now owned for themselves. His cousin Michael Harshaw lived in Pittsburgh where he was studying to be a Presbyterian Minister, something a poor boy without education could never do in Ireland.

He finished his circular trip by travelling from Pittsburgh to Cleveland, where he again traveled by lake steamers to Detroit and then back again to see his sister one more time. In the middle of the summer, he returned to New York City, and took the Great Western back to England. He had seen and learned much on this long trip, things that helped form the political ideas that governed much of the rest of his life.

View John Martin in America in a larger map

Sources: Dr. Hyde Salter, Asthma; Philip Hone's Diary; Dickens American Notes: P. A. Sillard, Life of John Martin.; Great Western background

Monday, June 6, 2011

Searching for John Martin

Please forgive any mistakes in the following post as it is translated by my Granddaughter in the sun room of our B&B in Northern Ireland and she finds my handwriting quite mysterious.

Actually, the secrets of John's life cannot be found in this tranquil place. They are to be found in the libraries of Irish cities. So I went first to the National Library in Dublin to search for information on miles of microfilm for John's public letters, and folders of private letters he wrote to friends, and out of print books written by contemporaries.

This time I found Dublin agog over other visitors: the Queen of England and the President of the United States. Security concerns made actual spotting of the visitors difficult, but I could tell they were nearby when helicopters hovered overhead or streets were closed to traffic. But research went on pretty much undisturbed.

I held no expectation for major discoveries, after all I had read most Irish newspapers published during John's years of political leadership and had finished the last folio of John's letters at the end of the last trip.

However, on Friday May 20th, I learned I had set my expectations far too low. A new search program revealed references that I had not yet read. When I arrived at the manuscript library that morning, I found several documents ready for me to explore. The young woman at the desk asked me which one I wanted to work with first. 'It doesn't matter at all,' I replied.

So she handed me the thin green book that topped the pile and I carried it to my favorite desk by the window. This unfamiliar source was titled Letters of Thomas F Meahger. It contained letters from a number of Irish leaders including John Martin. According to a newspaper article from 1948 attached to the front of the book, the letters had been discovered in Australia and given to Eamon Devalara to return to Ireland.

I settled in to read the letters John had written. He always wrote in clear but very small handwriting so there was much information per page. One of the first letters in the collection was one that John wrote from Paris on December 5th, 1854. It contained a stunning surprise about John's life that made clear how much he had sacrificed to serve his country. A routine research trip had suddenly become a very special adventure instead.

Saturday, May 14, 2011

Mystery Man of Irish History

John Martin and his role in Irish history has been almost completely forgotten. In many histories, he is missing entirely. In others, he is a single phrase or a footnote. As writers would have reported in his day, he has faded into oblivion. This is a strange fate for someone who was a national leader for many years and well known, respected and loved in many parts of the world.

Suzanne Ballard, a direct descendant of one of John's brothers, was the first sleuth in recent history to attempt to rediscover the truth of John Martin's life and contributions to his country. She was relentless in her search for any reference to his life and work. There was indeed a lot to find. She found references to him in books written by many of the leaders of his day. But she also discovered that John had left a great body of material, letters to friends and newspapers, speeches, even a personal journal which Suzanne transcribed. The John Martin her research discovered was a thoughtful and wise man. Though he was never strong or well, he spent every ounce of his energy in selfless service to Ireland. His high standards appealed to friend and foe alike. And at one point in his life, he was the most important man in Ireland.

One of the people with whom John carried on a long correspondence was William O'Neill Daunt. He was the personal secretary of Daniel O'Connell. Like John, Daunt remained politically active for his entire life. This quote comes from a letter John wrote to Daunt on April 28, 1866. It was a time when political changes for Ireland were being discussed with the idea that they would make Ireland more democratic and Irish independence less necessary. One initiative was the creation of universal suffrage, the other the secret ballot.

John wanted his friend to be clear about his own ideas. He described himself as a "CONSERVATIVE." He then went on to describe how he defined the word. "my preoccupation as a politician would be that all the citizens be equal before the law and that the law be really the will and voice of the whole nation in all its classes. This might exist under a fine monarchy, and it might not exist under the fairest & freest seeming constitution that liberals can invent. It is REALITY that I care for, & not very much the form. Besides I hold that the rich, the strong, the cunning can and will always deal unjustly with the poor, the feeble, the simple, if both be left perfectly “free.” And therefore I would endeavour to protect these latter. And I would see that as much by legislation as by institutions which leave unshaken and which nourish and strengthen the policy’s of moral responsibility." These ideas from 150 years ago can contribute in the political debates of today.

Tomorrow, I am leaving for Ireland on another search for more information on John Martin. For the next two weeks, I'll be hunched over a microfilm reader in the National Library in Dublin, reading newspapers published over 150 years ago. I had planned the trip and booked my tickets months ago. Only well after the fact did I discover that I would be in Dublin at a most interesting time. While I'm there, Queen Elizabeth will make an official visit, the first time a King or Queen of England has visited in almost 100 years. She will be joined also by Prime Minister of England David Cameron. The 10,000 troops which will be on hand for security will have just begun to rest up when another visitor arrives. Barack Obama will be making his first trip to Ireland a few days later. The Irish Parliament building is next door to the National Library, so I should have a good view of the visitations. If I can, I will be sending back posts of my discoveries about John Martin, and my adventures with the visiting dignitaries.

Then I'm traveling north to John's home territory for the opening of a special exhibit in the Newry and Mourne Museum called "A Great Change - the Lives and Times of James Harshaw, John Mitchel, and John Martin." James Harshaw was John's Uncle Harshaw. For the first time, visitors will be able to see the original journals both of these men kept. This exhibit will be open until the end of November, so many visitors will be able to take advantage of this very special opportunity.

Look for my next post from Ireland.

Suzanne Ballard, a direct descendant of one of John's brothers, was the first sleuth in recent history to attempt to rediscover the truth of John Martin's life and contributions to his country. She was relentless in her search for any reference to his life and work. There was indeed a lot to find. She found references to him in books written by many of the leaders of his day. But she also discovered that John had left a great body of material, letters to friends and newspapers, speeches, even a personal journal which Suzanne transcribed. The John Martin her research discovered was a thoughtful and wise man. Though he was never strong or well, he spent every ounce of his energy in selfless service to Ireland. His high standards appealed to friend and foe alike. And at one point in his life, he was the most important man in Ireland.