By Saturday, October 7, 1843, many Irishmen from Meath, Kildare and Dublin were already marching in good military form toward Clontarf. Just before dark, a message was delivered to Daniel O’Connell and his supporters that the British government had decided to declare the meeting illegal. O’Connell immediately submitted to the proclamation of the British, dispatched riders to inform the marchers that they were to return home. It was a great testament to the Irish people that such an about-face could be effected without any conflict. On Sunday, at the time the meeting was to take place, only British troops occupied the field, beach and sea beyond. Daniel O’Connell instead was in Dublin where he held a meeting to vote for the resolutions intended for Clontarf. The usual post-meeting banquet took place in Dublin as planned.

The actions that O’Connell took seemed like the worst of all possible solutions O’Connell’s speeches had led his supporters to expect a brave confrontation with the British government. Instead, they had gotten a meek surrender. The Young Irelander part of the Repeal Association was particularly upset. Some of them believed that the march should take place to test whether or not the British troops would fire on unarmed men. Others believed that Daniel O’Connell and his closest supporters should appear at the field to offer themselves for arrest.

John Martin’s friend from Newry, John Mitchel, had a more militant solution. O’Connell should lead the country marchers to Clontarf. However, the Dublin Repealers should be kept back in Dublin to stage an uprising, seizing the weapons at the Castle Barracks, destroying the Canal Bridge, and barricading the streets leading to Clontarf. Mitchel believed these acts could succeed as Dublin, for a short time would be undefended.

But, O’Connell had no wish to take any such dramatic actions against the British no matter how greatly he excited the Irish. Despite the fact that many Young Irelanders had suspected that O’Connell was more bluff than bluster, they were still bitterly disappointed at the fallout of Clontarf. British jubilation at their great triumph over the Irish was bitter enough. But worse was the recognition that O’Connell would never achieve Irish independence. They believed that O’Connell had pursued policies that led to a choice between “hopeless resistance or abject submission.”

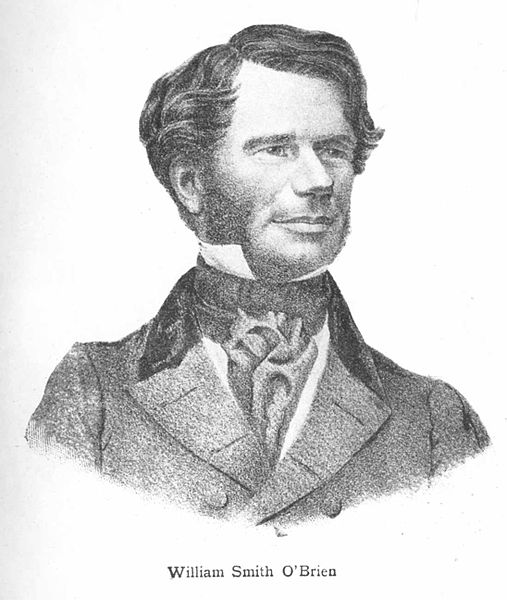

O’Connell went ahead as though nothing negative had occurred. For a few days, new memberships poured into the Association. One of the new members was William Smith O’Brien who had pled Ireland’s cause before Parliament in July. In the letter which accompanied his application for membership in the Repeal Association, O’Brien wrote, “Ireland, instead of taking its place as an integral part of the great empire which the valor of her sons has contributed to win, has been treated as a dependent, tributary province; and at this moment, after forty three years of nominal union, the affections of the two nations are so entirely alienated from each other, that England trusts the maintenance of their connection, not to the attachment of the Irish people, but to the bayonets that menace our bosoms and to the cannon which she has planted on all our strongholds. I should be unworthy to belong to a nation which may claim at least as a characteristic virtue that it exhibits increased fidelity in the hours of danger. If I were to delay any longer to dedicate myself to the cause of my country, slowly, reluctantly convinced that Ireland has nothing to hope from the sagacity, the justice, or the generosity of the English Parliament, my reliance shall henceforth be placed upon our own native energy and patriotism.”

Business as usual ended on October 12, when the British arrested O’Connell and 8 others, including Charles Gavan Duffy, the publisher of The Nation.

All of the accused quickly posted bail, so they could be present on October 22nd for the opening of the headquarters of the Repeal Association. It was located on Burgh Quay next to the Corn Exchange where the Repeal Association had been meeting since its founding. Conciliation Hall, as O’Connell named it, was an oblong building with the entrance on the shortest side facing the river Liffey. The outside was fairly simple, pilasters leading to a balustrade above. A harp and crown chiseled into the stone was the only other ornamentation. The inside was grander and arranged to ensure that O’Connell was always the center of attention.

While the finishing touches were being put on Conciliation Hall, the dispirited Young Islanders discussed what actions they could take next. They knew that O’Connell didn’t like opposition, so silence from the group was the simplest course. Still, they had contributed greatly to the powerful group the Repeal Association had become, and they believed O’Connell had wasted that power.

After much discussion, they decided that they wouldn’t oppose O’Connell’s leadership, but would make clear they dissented from his decision to retreat at Clontarf. They reasoned that any breach between them and O’Connell could be healed later. Since a quarter of a million men and women across Ireland read The Nation, they resolved to use the paper to make their position clear. Thomas Davis summed up the Young Irelander position, “Retreat would bring us the woes of war, without its chances or its pride.”

Unfortunately, these earnest young men could not know how deadly this split in the forces of nationalism would be in two short years.

The trial of the 9 men accused of conspiracy against England dragged on for months before a carefully selected jury that favored England. On May 30, 1844, all men were convicted and removed at once to Richmond Prison. John Martin immediately traveled to Dublin and joined the Repeal Association. With that action, John became a political figure of importance for the rest of his life.

John Mitchel wrote to Duffy in Richmond Prison about this new member. Mitchel told Duffy that Presbyterians were beginning to join the Association in small numbers, “some from patriotic motives, and some from party ones, some from high, some from shabby ones, will join the conspiring for old Ireland. But if there be a single member of the Association that has joined it for the pure love of justice and of his native land that one is John Martin.”

|

| The 9 Accused of Conspiracy |

Sources: Last Conquest of Ireland (Perhaps) by John Mitchel; Life of John Mitchel, by William Dillon; Young Ireland, a Fragment of Irish History, by Sir Charles Gavan Duffy.